China’s quick way of going green: cutting production to cut emissions

The country’s energy-intensive industries have been told to cut output. Alexander Brown says this shows Beijing’s climate pledges are no empty talk, though fulfilling them will be tricky.

China’s headline-grabbing power outages and curbs on manufacturing are clear signs that Beijing is serious about reducing the volume of greenhouse gases it pumps into the atmosphere. It pledged a year ago to reach net-zero emissions by 2060, launched its first national carbon emissions trading market in July, and just issued its roadmap for carbon neutrality. Yet its orders to limit production stand the best chance of cutting pollution in the short term – although how much economic growth it is willing to sacrifice remains to be seen.

Beijing has emissions cuts firmly in its sights

China’s reliance on coal to power energy-guzzling industries like steel, aluminum, and cement is a key obstacle to its decarbonization. In 2019/2020, the country produced over half of the global production of these commodities: 56.7 percent of crude steel, 55 percent of cement, and 57.2 percent of aluminum. According to current estimates, these industries account for over a quarter of China’s total carbon dioxide emissions, with steel alone accounting for at least 15 percent. But, however daunting, Beijing has emissions cuts firmly in its sights.

Cracking down on “dual high” projects – a reference to high energy consumption and high-emission projects – was established as a national priority for the first time in the 14th Five-Year Plan. Released in March this year, the document identifies the iron and steel, non-ferrous metals, and building materials industries as sectors due for restructuring and a green transformation. In line with this goal, China had three months earlier vowed to “resolutely reduce” crude steel output to keep production this year below 2020 levels.

Industrial production picked up strongly in the initial months of 2021, contributing to China’s economic recovery, but making the government’s task of reducing output more difficult. In an effort to curb high-polluting domestic manufacturers, Beijing responded in May by lowering the import tax rate to zero and sharply increasing export tariffs for several energy intensive products. And it subsequently insisted on provincial energy intensity and energy consumption targets being met, essentially proxies for keeping carbon emissions in check. In the first half of the year, 20 out of China’s 30 provincial-level governments failed to meet these targets. The central government named and shamed the worst offenders and issued a new policy document reasserting the importance of curbing energy consumption. This appears to have prompted the desired response. Reports about local governments intervening to meet their energy targets have been piling up – indeed, some suggest that a mad scramble to comply on the part of some contributed to wider power outages.

Steel, aluminum, and cement producers have faced output cuts

Steel producers in provinces such as Jiangsu, Shandong, Liaoning, Yunnan, and Fujian have faced output cuts in recent months. Cities across northern China have been told to cut steel production throughout the coming winter to limit air pollution and meet output reduction targets. China’s primary steel base, Hebei province, is reportedly the only region on track to meet its annual steel output target. Strict cuts in its city of Tangshan, also known as the steel capital of China, have limited production since they were implemented in March.

A similar trend is evident in the aluminum and cement sectors. At the start of the year, the provincial government of Inner Mongolia curbed aluminum-smelting capacity in the city of Baotou to meet quarterly targets. In late August, China’s southwestern province of Guangxi ordered producers of aluminum, alumina, steel, ferroalloys, and cement to cut output. Yunnan told its cement industry to cut September production by more than 80 percent from August and aluminum smelters to stay below August volumes in the three months after that.

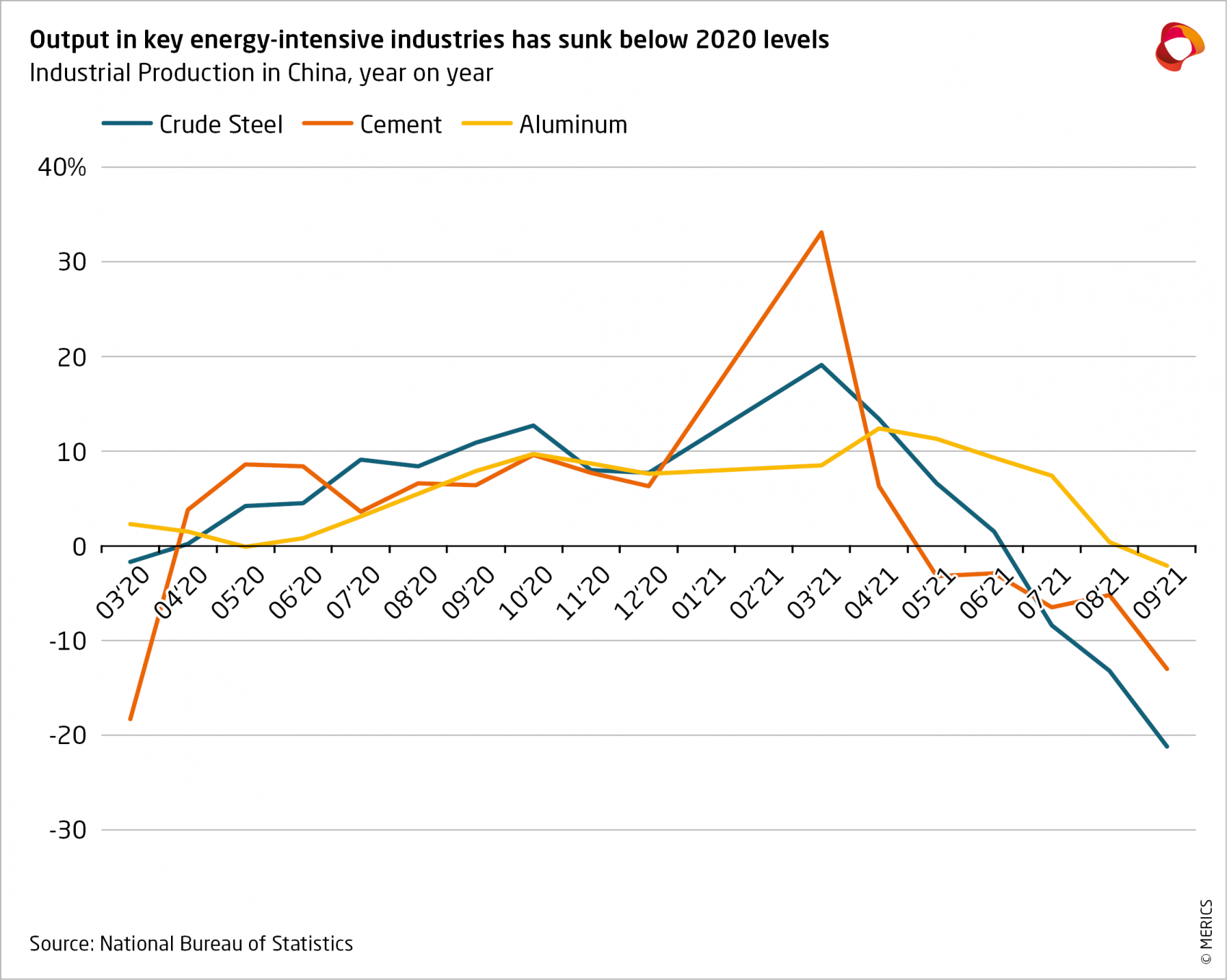

The latest data shows that production of steel, aluminum, and cement began to decline in the third quarter as a result (see exhibit). By the end of September, tightening emissions standards and the energy supply shortage began to wreak havoc on manufacturing. About 7 percent of aluminum production capacity was suspended and 29 percent of cement production affected. While energy shortages have recently made headlines, the role of energy intensity and consumption targets in output decline should not be underestimated.

Short-term pain could lead to long-term gain

Facing widespread power cuts and fuel shortages, the government must now juggle competing priorities. Its moves to increase coal supplies reflect energy security concerns, but will drive up emissions. Yet not all solutions are so double edged: relaxing caps on electricity prices has allowed them to rise, boosting electricity generation and putting sustained pressure on energy-intensive industries to cut consumption. Short-term pain could also lead to long-term gain, if curbs on traditional industries lead to investments in efficiency and low-carbon technology.

For Beijing, maintaining China’s strength as a manufacturing base and combatting climate change go hand in hand – energy-intensive industries just have to become greener. For instance, the government is working on a strategy for the iron and steel sector that reportedly aims to have emissions peak before 2025 and then fall 30 percent by 2030. Clean energy sources will be important for this, but so will ongoing output cuts. At least in the short run, reducing emissions will come at an economic cost, so more disruption is likely in the months ahead.

To pick up the resulting economic slack, service industries and consumer demand will need to become China’s new growth drivers in the coming years. But the government so far has had limited success in accelerating the transition to an economy driven by domestic demand. The slower this switch, the more reticent Beijing could become about dampening economic activity in high-polluting sectors. Decarbonization will not be easy and China will not pursue it at any cost. But its current efforts show that Beijing’s carbon pledges are not empty talk.